Discovering Dombrovsky

By Sarah J Young, on 17 January 2014

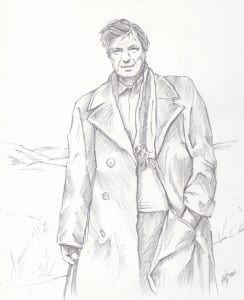

Yuri Dombrovsky by Gregory Lindsay-Smith.

© Gregory Lindsay-Smith.

Reproduced with permission of the artist.

Jekaterina Shulga reflects on the work of an extraordinary Soviet writer, Yuri Dombrovsky, and the limitations of formal literary analysis for dealing with such an unusual figure.

I remember the first time I read Yuri Dombrovsky’s novel The Keeper of Antiquities well. I was exploring writers to research for my thesis on trauma and narrative. Trauma seemed to be absent from this novel, but it had something else and I couldn’t put my finger on exactly what. And this is how Dombrovsky writes, always with a surplus, making us feel that there is forever more to it than meets the eye. That convinced me that he is one of the greatest Russian writers of the 20th century, but he has never achieved the attention or recognition he deserves. Although most Russian literature scholars will nod their heads and smile when you mention Dombrovsky, usually followed by “I really like The Keeper” or “he’s really interesting”, very few have researched or written about him. Most of what we know about Dombrovsky comes from a small number of sources and often it is based on anecdotal evidence. People want to talk about what he was like, not where he lived or what he did.

This is because Dombrovsky really was a fascinating character. He lived during the most repressive time in 20th-century Russia, and yet he remained rebellious, defiant and a lover of freedom. Born in 1909 in Moscow, he became interested in literature as a young boy, a passion would sustain him throughout his life, giving him the strength to fight for what he believed was right, even though it came at a great cost to himself. However, his righteousness was also infused with a large portion of rebelliousness and defiance. He often referred to himself as a gypsy and a hooligan. This is no Solzhenitsyn-like prophet.

In 1932, soon after starting his studies in literature he was arrested and exiled to Alma-Ata (now Almaty), where he lived until 1956. During his exile he worked at the remarkable Zenkov Cathedral, which had been turned into a museum, and taught literature and drama at various institutions. He was arrested a further three times, spent several years in the hard labour camps of Kolyma and elsewhere, and was released as an invalid. It took Dombrovsky many years to recover from these experiences, but he rarely writes about the Gulag. It is only in his poetry that we catch a glimpse of this dark period in his life. But even here there is a contrast between the terrifying subject of the camps and a light and cheerful rhythm and rhyme. Similarly, his fiction represents the darkest period of Stalin’s oppression in a surprisingly colourful and engaging manner.

His two major novels, The Keeper of Antiquities and The Faculty of Useless Knowledge, are both set in Alma-Ata and depict the life of a museum keeper working for the central Kazakhstan Museum in the Zenkov Cathedral. The novels are largely based on Dombrovsky’s life, yet they are fictional and blend his own experiences with his artistic expression. Dombrovsky suggested that some things are difficult to speak about oneself, so it seems that fiction allowed him to delve into his experiences in a deeper way.

Although Alma-Ata is the place of his exile, it becomes the beautiful setting in which the terror of 1937 unfolds, and plays a large role in the book. The narrator of the novel, Zybin, describes to the reader the many writers, intellectuals and architects who have lived here and created the city. Everything for Zybin is a treasure to be remembered and understood. He is known as the keeper of the museum, located in the Zenkov Cathedral. All he wants is to be left alone in the attic of the museum to pursue his interest in history, archaeology and art. But to be left alone to research art and history independently proves to be impossible during Stalin’s terror.

Although both novels represent daily life during Stalin’s terror, they do this in a strangely bright and fantastical manner. It is hard to draw the line between where the mundane and absurd bureaucracy ends and the fantastical begins. The main plot ofThe Keeper revolves around Zybin’s involvement in an odd story about a boa constrictor that has escaped the circus and is roaming the hills in Alma-Ata, wreaking havoc on the apple harvest and terrifying everyone in its path. How a boa constrictor could survive a winter in the mountains is unclear, but people are inclined to believe the story, and an absurd search for the snake begins. (The peasant who has seen the snake repeatedly calls it “boa constructor”, mixing comedy with the terror). Zybin finds the story ridiculous, yet it is taken seriously by the authorities, so it becomes a matter of state interest and important, even dangerous, to all involved.

This story develops alongside Zybin’s archaeological discovery: he has found traces of gold from a mysterious burial ground belonging to an ancient maiden. This story continues in the sequel The Faculty of Useless Knowledge, where Zybin attempts to find out the truth about the burial ground. His archaeological pursuit clashes with the authorities’ interest in the value of the gold – they have no interest in its historical meaning. Zybin’s life comes under attack when this gold is stolen from the museum and he is implicated in its disappearance. He is arrested and interrogated by the Alma-Ata secret police, and the mindless terror of the Soviet regime becomes apparent as interrogators try to get Zybin to implicate himself in the crime so that they can hold a public trial. It emerges that the authorities are planning to create a spectacle on the scale of the Moscow trials and Zybin is their main actor. Despite depicting the horror of the interrogation system, Dombrovsky also shows Zybin’s unbreakable sense of freedom. He never bows down to authority and remains true to himself, finding his strength in the now useless knowledge of history and creativity, which he sees as the path to truth.

There is a constant balance in the novels between the eternal/universal view and the small and specific. The Stalinist terror is set in the context of the terror of ancient Rome, and Zybin’s fate is part of that long history of mankind. This all-embracing view of time allows Dombrovsky to infuse the novel with art and literature of all eras. One of the great pleasures of reading this novel is the constant learning process through which Dombrovsky puts you, as you chase up his many allusions to artists and writers, his historical references and literary quotations. Looking up each opens up further secret doors in the novel, and you discover new and deeper meanings. He will tell you about Alma-Ata, about its teachers, thinkers and artist. One of my favourite is “The genius of First Rank of All the Galaxies” – and that is what he calls himself – Sergey Kalmykov (1891-1967). This artist stands on the streets of Alma-Ata in colourful outfits painting life, and raising a not a few judgemental eyebrows. The contrast of this colourful individual to the darkness of Stalinist terror is what makes these novels so remarkable.Dombrovsky celebrates beauty and humanity, whilst depicting its eradication by the State. But he never does this didactically; he often contradicts himself and confuses the reader, but ultimately leaves us with the clearest idea of what it means to be human, and he does so with a cheeky grin.

Dombrovsky managed to get The Keeper of Antiquities published in 1963. It slipped through the censorship shortly after One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, before the doors on the more liberal novels were closed. The Faculty of Useless Knowledge, however, was written in secret for 11 years, and recognizing its controversial nature, Dombrovsky decided not to attempt to publish it in the Soviet Union but to send it abroad. The novel was published in Paris in 1978, two weeks after Dombrovsky had been violently assaulted on the stairs of the Writers’ Union in Moscow and died. Despite the abuse he suffered throughout his lifetime, Dombrovsky’s spirit remained unbroken and free. This is no small feat. This, his stubborn rebelliousness and his warm-hearted nature is exactly why it is impossible to write about him objectively and without emotion.

In The Keeper of Antiquities, Zybin says of the Alma-Ata painter Nikolai Khludov (1850-1935):

And the article I wrote about Khludov long ago was a failure simply because I too had tried to analyse him and generalise about him; Khludov suffers under such formal treatment. One should begin an article about him with the words ‘I love’. They are very precise words, and they at once put everything into the proper perspective. So – I love…

Similarly, it is impossible to write about Yuri Dombrovsky dispassionately. Standard forms of literary criticism can make this uncompromising and playful writer appears lifeless and ordinary. So – I love…

Jekaterina Shulga was awarded her doctorate for her thesis on trauma and memory in the narratives of Yuri Dombrovsky and Vasily Grossman at UCL-SSEES in January 2013. She is currently teaching Russian language and literature at Queen Mary.

Note: This article gives the views of the author(s), and not the position of the SSEES Research blog, nor of the School of Slavonic and East European Studies, nor of UCL

Close

Close